Stefan Vanthuyne

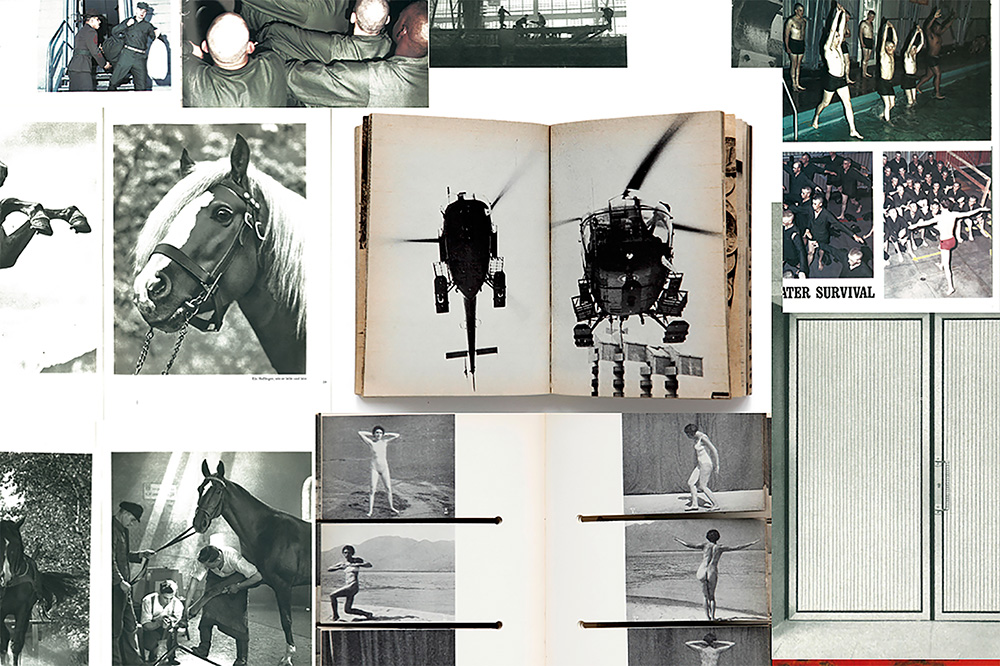

Erik Kessels, Terribly Awesome Photo Books, 2017

Last spring and throughout last summer the CCCB and the Fundació Foto Colectania in Barcelona hosted Photobook Phenomenon. The exhibition focused entirely on the photobook, highlighting its role in the history of photography and in contemporary visual culture. We spoke with executive curator Moritz Neumüller.

Next to Moritz Neumüller, who together with Irene de Mendoza set up a presentation of contemporary photobook practices, eight other international curators, all considered experts within the photobook field, worked on a specific chapter in the exhibition. Martin Parr, Magnum photographer and avid photobook collector, displayed a series of 57 high-quality publications from his collection, consisting over 13.000 pieces. They served as the red thread throughout the exhibition. Gerry Badger, together with Parr co-author of the influential trilogy The Photobook: A History, presented a collection of protest and propaganda books. Marcus Schaden and Frederic Lezmi, founders of the ongoing PhotoBook Museum project, analyzed the groundbreaking Life is Good & Good for You in New York by pasting the spreads from William Klein’s 1956 classic rhythmically onto two elongated walls, accompanied by colored markings and commentary. Ryuichi Kaneko, curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography and co-author of Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ’70s and more recently The Japanese Photobook, 1912-1990, focused his gaze on the long and rich photobook tradition in Japan.

Photobooks, or books containing photography, have been made for over a century. Photobook anthologies, the so-called books on books, have been around and have been piling up since early 2000. And though photobooks now are much more predominant in photography exhibitions than ever before, an exhibition as elaborate as this, focusing solely on photobooks as a cultural phenomenon seems new and unseen.

Moritz Neumüller: “The photobooks have indeed been around and they have been seen. It’s just that the people who write – or used to write back in the day – about photography are mostly academics who give a lot of value to exhibitions. Exhibitions have always been proof of a photographer’s influence or fame to the general public and to the critics. That is important. But also very important is the impact an artist has on other artists.”

“Picasso and Duchamp are what they are because they have influenced so many other artists. And many artists have created in direct dialogue with them. For more than a hundred years, photographers have been exchanging ideas through the book medium. Manuel Álvarez Bravo did not go from Mexico to Paris to visit Eugène Atget, but he did have a book of Atget’s work in Paris in his library. And when he also saw the books of Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson, he changed his practice. He became Manuel Álvarez Bravo, by looking at books. And that’s the case with many photographers. By looking at other people’s work, they got inspired; their eyes popped open and they said: ‘This is what I want to do!’. Not because they travelled the world looking at exhibitions, but because they saw the work in books. The books travelled.”

“So this has always been important for the photographers, but less so for the academics. It took somebody like Martin Parr, who is a photographer himself and who insisted for many years that photobooks are indeed very important for photography. So when Parr started curating exhibitions – one of the first was in Arles in 2004, I believe – he included many photobooks. He also references Horacio Fernández (curator of chapter 7 of the exhibition, The Library Is the Museum, ed.) as the one scholar who from the beginning understood the importance of the photobook – and of the printed image in general. His exhibition Fotografía pública from 1999 was the first to have a great impact.”

“Before, a photographer got crowned for his career with a big monograph that presents a selection of his best work. The new century and the changes in technology, making it much easier to print your own photobook, has turned that around. Nowadays young photographers, Christina de Middel for instance, start their career with a first book and then continue to build their career upon books. This evolution has sparked a need for a rewriting of the history of photography. Things have been coming together for the last fifteen years and today we can really map it as a cultural phenomenon.”

“Nowadays young photographers start their career with a first book and then continue to build their career upon books” (Moritz Neumüller)

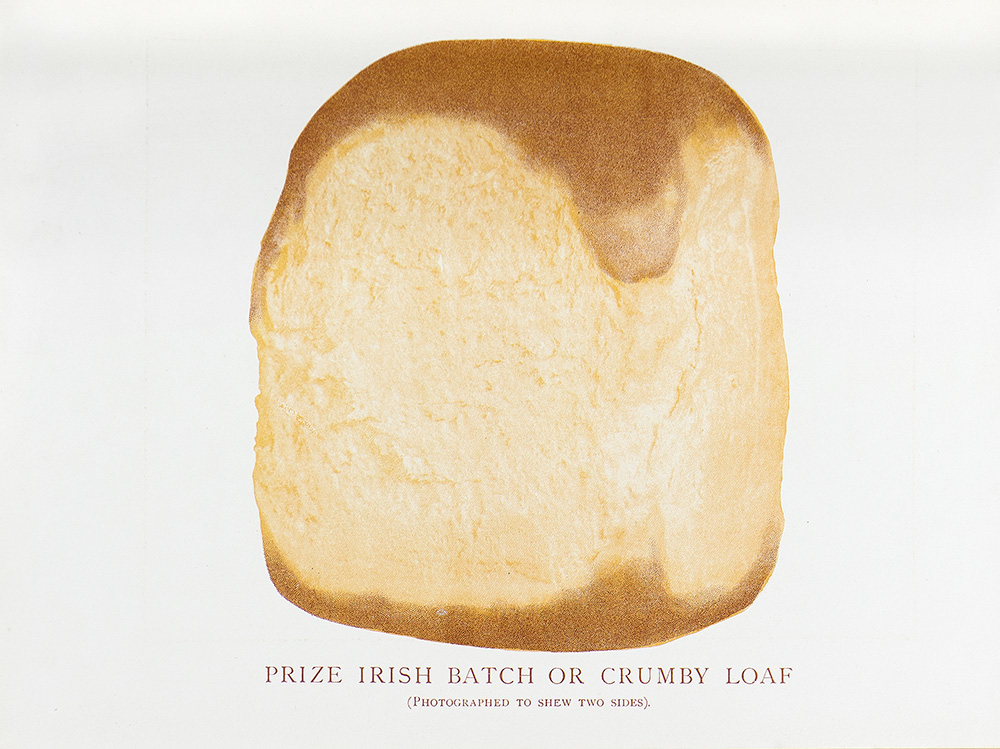

Owen Simmons, The Book of Bread, Maclaren and Sons, London, 1903

The first book in the exhibition is The Book of Bread (1903) by Owen Simmons, which is really a guide to bread-making. Just like Erik Kessel’s collection of manuals and hobby books, it is an ‘accidental photobook’, as Aperture’s Denise Wolff calls them. Other types of books that use photography, but are not considered photobooks qua photobooks because they are free from an artist’s agenda.

Neumüller: “That is an old subject in photography or in art, going back to the Wunderkammer. All kind of things, either man-made or nature-made, were collected and by collecting them became kind of valuable or interesting objects. If you go to any photography museum, you will find on the walls or in the collection photographs that were explicitly made with a non-artistic intention – to inform about something – but have now been recognized as works with great cultural meaning or as works of art, if you want. Of course The Book of Bread can be seen as a photobook, even if it was conceived as a manual for making good bread.”

“Take for example city books. Many people bought those books simply because of their interest in travel. Think about Die Blauen Bücher in Germany. Tens and thousands of people bought those for their library. But now more and more they are considered and treated as photobooks – because they are.”

Some say this is the golden age of the photobook, to others it is far from a golden age – for publishers, for example. How do you look at that discussion? Is it a relevant one?

Neumüller: “Most people who talk about the golden age of photobooks, are actually talking about the 50s, 60s and 70s. Because that’s when the really interesting photobooks came out. It is true that we do have more publishers, micro-publishers, independent publishers and self-publishers than ever. Therefore, since the market and the demand have not grown that much, yet the supply has grown, the print-runs have become very small. Publisher Dewi Lewis said that he used to have print-runs of 4000 or 5000, while nowadays if he prints 1000, it’s already a lot. Today you see a lot of books being printed in an edition of say 250. And when they sell out you get a new edition or a second printing, or maybe not. It is true that publishers had to adapt their business model. It’s simply not possible anymore to sell 10.000 books, because there are too many books around.”

“So is it a golden age? At least it is a time where a lot of people talk about photobooks and still a lot of people are buying photobooks. The public is more aware of the artistic possibility of the photobook and the photobook has become a cultural phenomenon worldwide. Especially in Europe, I would say. Less in America, still, always in Japan. It is a global thing.”

“Is it a golden age? At least it is a time where a lot of people talk about photobooks and still a lot of people are buying photobooks” (Moritz Neumüller)

You’ve curated the contemporary section in Photobook Phenomenon. What do you think is the strength of today’s photobook makers?

Neumüller: “The big strength of the contemporary photobook is its versatility. There are the books that Lesly Martin in her essay (in the Photobook Phenomenon catalogue, ed.) calls ‘bells and whistles’ books. Books that try to catch your attention with all sorts of design elements. There are so many ways in which you can make your book look attractive, to the point where it becomes mannerist or baroque – just too much, really. But then at the same time there are very solemn books as well. Today we have so many possibilities. You can choose very freely the format that goes best with the message you want to communicate.”

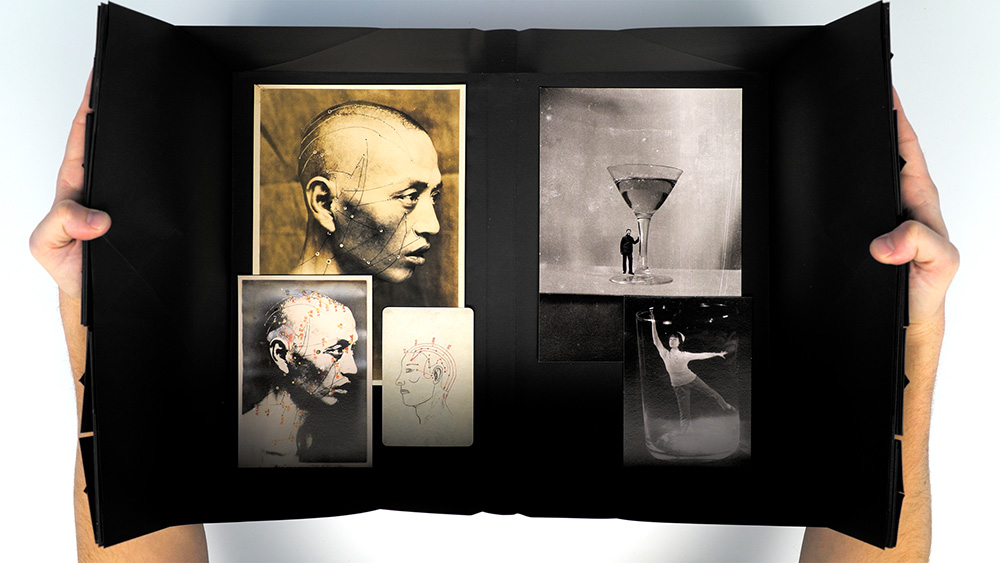

Thomas Sauvin, Xian, 2016

How do you look at the internet in regards to the photobook?

Neumüller: “In the exhibition we have some books on the Arab Spring. And the Arab Spring was only possible through the internet. Social media was essential in organizing the people in a very quick way and outside of the mass media owned by the state. The same happened in Syria, before the war really began. The images that people exchanged, were exchanged via the internet.”

“That however doesn’t mean that books aren’t necessary to store, present and represent these images in another form. The internet offers images in a connection of links that are non-directional and ambiguous, whereas the book has a first page and a last page. What happens in between can sometimes be like a film sequence. You can build a narrative through the book and narratives will always be more interesting in the book form.”

“Also, the book as an object will always be the way the author wanted it to be. If I send an image to your phone, the image will show in the way your phone wants it to show. The apparatus will decide how my image will look on your phone. But if I give you a book, the photograph will be in the way that I, the maker of the book, wanted it to be.”

How do you see the role of the contemporary photobook evolve in today’s society? At last year’s Unseen Dummy Award, juror Sean O’Hagan called photobooks the key medium of the moment. “The world is changing so chaotically and so ominously. Photography – and photobooks – cannot help but engage with the turmoil.”

Neumüller: “Photographers are looking to deliver the message in the way they want it to be seen. And in a way, they have more freedom to do that than in the days of Robert Capa. But with traditional media having no more staff photographers, they have to do it themselves or it doesn’t get done. There is a lot of work for photographers, but there are no more jobs.”

Content for this platform is written by non-native English speakers. If you find some flagrant mistakes, please don’t hesitate to let us know.

Photobook Phenomenon, installation view